From Aerial Imagery to Machine Learning

November 1, 2023Sitting Around the Fire

February 25, 2025Beyond Buildings and Roads

Community mapping initiatives are often considered tools for empowerment. Also known as participatory mapping, community mapping is a process where communities gather data and create maps representing their local knowledge, experiences, and perspectives. This approach includes social, cultural, and environmental information, and goes beyond traditional mapping.

However, in recent years, many initiatives that call themselves community mapping focus solely on mapping buildings, roads, and public amenities, leaving out the more complex social, environmental, and cultural dynamics. While mapping physical structures is important, it only scratches the surface of what community mapping can and should be.

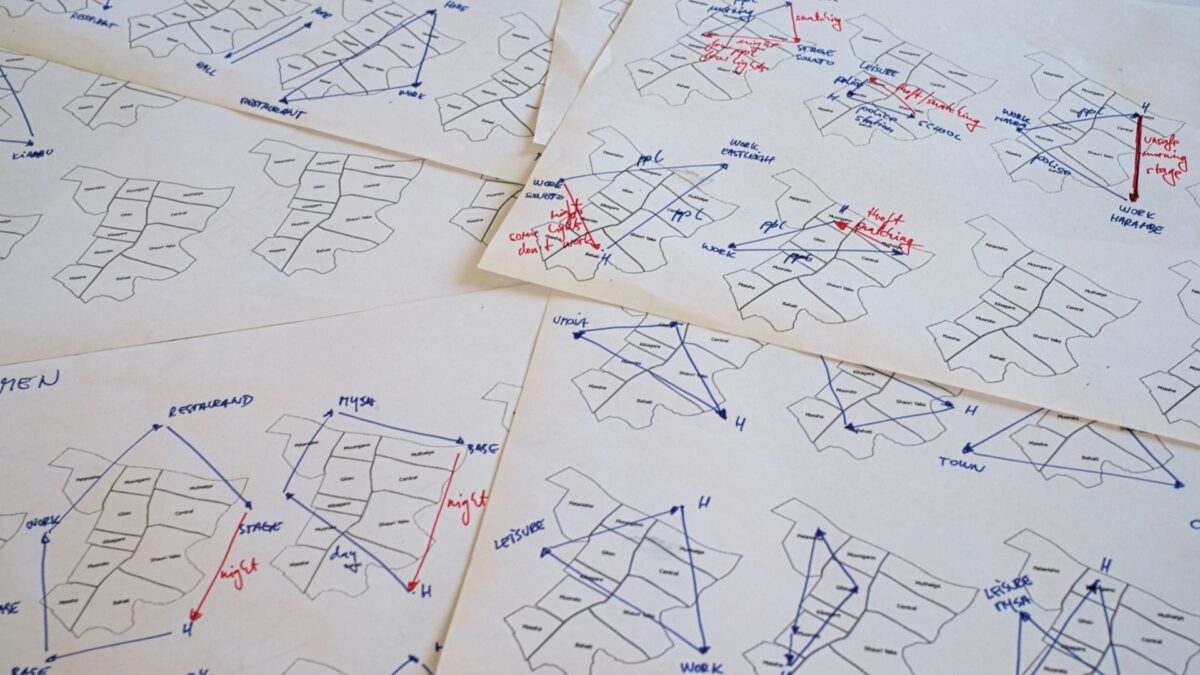

Community mapping is a deeper process than that of conventional mapping. It involves documenting people’s relationships, their links to the land, and their perceptions of both built and natural environments. It aims to understand people’s movements through space and time, the decisions they make, and what drives them, uncovering community dynamics, and documenting various types of governance initiatives. This human-centric approach reveals the complex pattern of a community’s life and its interaction with the environment.

Our most successful projects have been those that focused on this more human-centric approach. Here are a few examples:

Documenting Community Land Rights in Southern Kenya

In Tana River County, Kenya, we worked on a project to document community land rights. This wasn’t just about marking boundaries on a map, it was about understanding the deep, often complex relationships people have with their land. We recorded resources they found valuable, including sacred sites and religious locations, natural features, and natural resources, as well as stories of inheritance, pressures, and inter-communal agreements that have shaped the community’s landscape. These were some of the first maps of community land ever created in Kenya. This kind of mapping helps protect these rights and ensures they are recognized and respected by authorities.

Land Adjudication in Zanzibar

Following our community land mapping project in Tana River, we worked in Zanzibar with the Commission for Lands to delineate and document individual properties for issuance of title deeds. Moving from traditional paper-based techniques to digital technologies such as drones, tablets, and cloud-based solutions, we engaged with property owners, their neighbors, and government officials to accurately map properties and people’s relationships to the land and community. This modern approach not only accelerated the adjudication process but also reduced the cost per title, resulting in the successful documentation of 1,000 landowners and the issuance of land titles by the government.

Impact of Development Projects on Livelihoods in Lamu

In Lamu, northeast Kenya, we documented how the construction of a new port affected the livelihoods of local populations, including fishermen, pastoralists, farmers, traders, and those in the tourism sector. Our mapping efforts extended beyond the physical structures of the port to include the social and economic impacts it created. We documented fishing routes, fish landing sites, pastoralist routes, watering holes, natural habitats and protected areas, agricultural areas, and other resources vital to communities’ livelihoods. After this initial data collection, we superimposed the port’s location and its amenities onto the maps, revealing potential future conflicts. The communities used these maps to advocate for compensation from the government. This type of initiative helps us promote more inclusive and sustainable development practices.

Perceptions of Safety in Informal Settlements

In informal settlements in Nairobi, we mapped people’s perceptions of safety and collaborated with local leaders to document individual instances of crime. This involved gathering stories and experiences from residents about areas where they felt safe or unsafe, understanding the reasons behind these perceptions, and pinpointing hotspots and difficult-to-navigate areas. This type of mapping was crucial for planning interventions that improve safety and security in these communities.

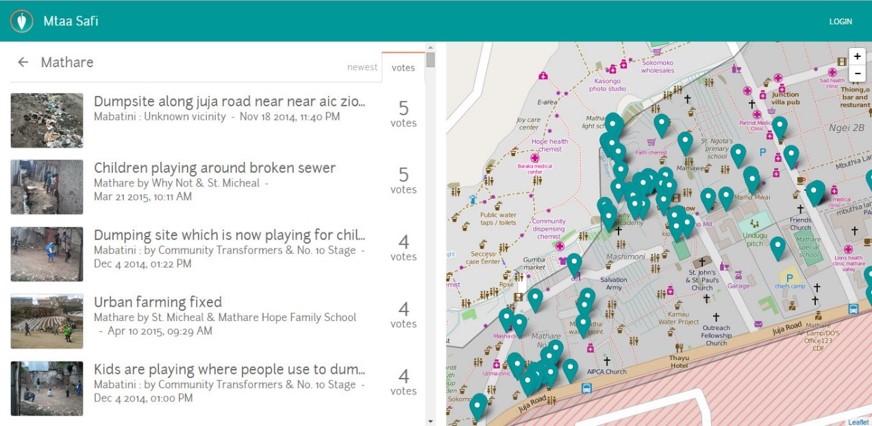

Waste Collectors in Mathare

In Mathare’s informal settlements, we collaborated with more than fifty waste collectors, primarily youth groups, to understand the dynamics of waste management in areas lacking formal services. We investigated who provides waste management, the clients they serve, their earnings, their beneficiaries, service areas, financial supporters, links to the government, whether they offer recycling services, and their use of technology to coordinate activities. This mapping highlighted the crucial role these informal workers play in the environmental management of cities, maintaining cleanliness and promoting sustainability in their communities despite the lack of formal recognition or support. The data was subsequently presented to the government with solutions to improve service delivery, including the introduction of more trucks for waste collection and removal.

Lessons Learned

Successful community mapping should go beyond the documentation of physical structures or natural features. It should look into the heart of the community, capturing the human relationships, cultural narratives, and socio-economic characteristics.

Here are some of the lessons we learned from our past experiences that showcase the potential of human-centered community mapping:

- Community mapping should capture the social, cultural, and economic community dimensions to provide a holistic view of the community.

- By documenting relationships and narratives, we gain a better understanding of the community’s needs and dynamics.

- When people share their knowledge and stories, the data becomes a powerful tool for advocacy and change.

- By considering the livelihoods of populations we can mitigate potential risks and future conflicts.

- Understanding, recognizing, and supporting existing governance initiatives — both formal and informal — can improve service delivery, environmental and resource management, and sustainability.

- Embracing technological advancements and a technology-agnostic approach can significantly improve the data quality.

- Community mapping should not be an end in itself but a means to generate actionable insights.

- The collected data must inform policy, guide interventions, and drive positive change within the community.

- The collected data must provide concrete evidence that communities can use to engage with authorities, demand their rights, and influence policy decisions.

- The most successful community mapping projects involve collaboration between community members, local leaders, government officials, and experts. All of our most impactful projects have had this link well established.

Final Thoughts

We recently had a conversation with a very talented young mapper and developer from Kibera, often referred to as sub-Saharan Africa’s largest slum. We discussed how Kibera has been mapped ten times over in recent years, yet the area still looks much the same as it always did. It’s hard to see how these initiatives improve the settlement. This raises an important question: Are organizations collecting the right data for the right purpose?

It might sound critical, but nowadays, every development organization that has heard mobile phones can be used to collect data is jumping on the bandwagon. This has led to an oversaturation of “community mapping” initiatives, producing both valuable and often questionable data that sometimes seems to be collected for its own sake rather than for meaningful action.

Let us clarify: We fully advocate for widespread participation in development, knowledge sharing, and the democratization of technology, ensuring it’s accessible to everyone. We believe in the power people have over their own lives. However, as experts dedicated to sharing knowledge and supporting people and organizations in collecting and utilizing meaningful data, we are strongly against simplifying our work to the point of ineffectiveness. Communities deserve to learn from the best and have access to technology and methodologies that can drive positive change. By providing stripped-down knowledge and information, we are doing them a disservice. As professionals supporting communities, we must equip them with all the tools at our disposal to truly help them improve their lives.

Community mapping should be more than a technical exercise; it should be a tool for storytelling, advocacy, and empowerment. It should capture the fundamental quality of the community’s lived experience and translate it into actionable insights. We urge fellow practitioners to look beyond the physical structures and natural features and dive into the human stories that define our communities. Only then can we truly leverage the power of community mapping to contribute to meaningful change.